Arguments

- Immutable arguments are effectively passed “by value.”

- Mutable arguments are effectively passed “by pointer.”

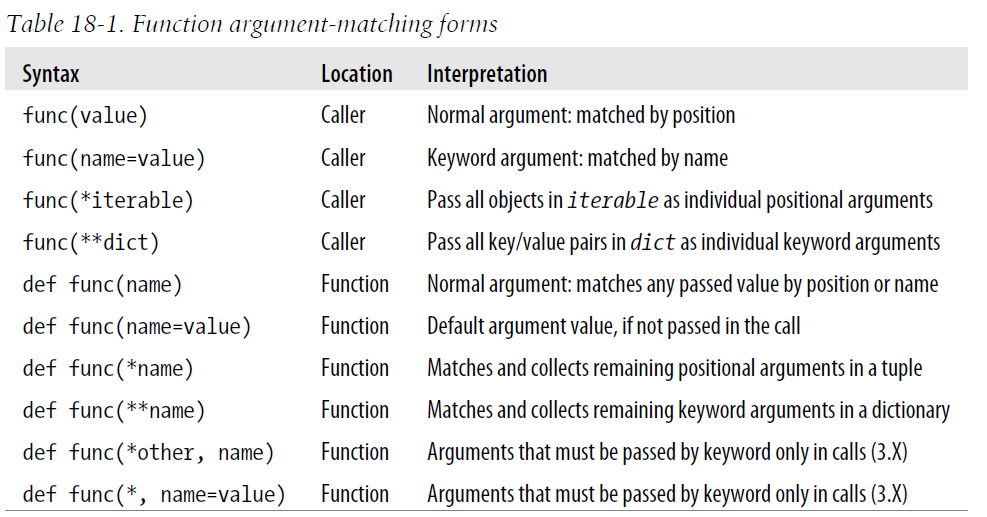

Argument Matching Syntax

image_1angt2tti1eku1fmm1dqau5q1riom.png-143.4kB

image_1angt2tti1eku1fmm1dqau5q1riom.png-143.4kB

Headers: Collecting arguments

def f(*args): print(args)

f()

# ()

f(2)

# (2,)

f(1,2,3,4)

# (1, 2, 3, 4)

def f2(a, *pargs, **kargs): print(a, pargs, kargs)

f2(1, 2, 3, x=1, y=2)

# 1 (2, 3) {'x': 1, 'y': 2}

Calls: Unpacking arguments

def func(a, b, c, d): print(a, b, c, d)

args = (1, 2)

args += (3, 4)

func(args)

# func() missing 3 required positional arguments: 'b', 'c', and 'd'

func(*args)

# 1 2 3 4

func(*(1, 2), **{'d': 4, 'c': 3})

# Same as func(1, 2, d=4, c=3)

Recursive Functions

First Example

def mysum(L):

if not L:

return 0

else:

return L[0] + mysum(L[1:])

print(mysum([1, 2, 3, 4, 5]))

# 15

Another Example

def mysum(L):

first, *rest = L

return first if not rest else first + mysum(rest)

print(mysum(('s', 'p', 'a', 'm')))

# spam

A example of handling arbitrary structures

def sumtree(L):

tot = 0

for x in L: # For each item at this level

if not isinstance(x, list):

tot += x # Add numbers directly

else:

tot += sumtree(x) # Recur for sublists

return tot

print(sumtree([[[[[1], 2], 3], 4], 5]))

# 15

Also note that standard Python limits the depth of its runtime call stack—crucial to recursive call programs—to trap infinite recursion errors. To expand it, use the sys module

>>> sys.getrecursionlimit() # 1000 calls deep default

1000

>>> sys.setrecursionlimit(10000) # Allow deeper nesting

Indirect Function Calls: “First Class” Objects

def make(label): # Make a function but don't call it

def echo(message):

print(label + ':' + message)

return echo

F = make('Spam')

F('Eggs!')

Exception Basics

If you don’t want the default exception behavior, wrap the call in a try statement to catch exceptions yourself.

def fetcher(obj, index):

return obj[index]

x = 'spam'

try:

fetcher(x, 4)

except IndexError: # Catch and recover

print('got exception')

So far, we’ve been letting Python raise exceptions for us by making mistakes (on purpose this time!), but our scripts can raise exceptions too.

try:

raise IndexError # Trigger exception manually

except IndexError:

print('got exception')

As you’ll learn later in this part of the book, you can also define new exceptions of your own that are specific to your programs.

class AlreadyGotOne(Exception): pass # User-defined exception

The try/finally combination avoids this pitfall—when an exception does occur in a try block, finally blocks are executed while the program is being unwound.

def after():

try:

fetcher(x, 4)

finally:

print('after fetch')

print('after try?')

after()

# after fetch

# Traceback (most recent call last):

The with/as statement runs an object’s context management logic to guarantee that termination actions occur, irrespective of any exceptions in its nested block.

with open('lumberjack.txt', 'w') as file: # Always close file on exit

file.write('The larch!\n')

Managed Attributes

That’s one of the main roles of managed attributes—they provide ways to add attribute accessor logic after the fact. More generally, they support arbitrary attribute usage modes that go beyond simple data storage.

Four accessor techniques:

- The __getattr__ and __setattr__ methods, for routing undefined attribute fetches and all attribute assignments to generic handler methods.

- The __getattribute__ method, for routing all attribute fetches to a generic handler method.

- The property built-in, for routing specific attribute access to get and set handler functions.

- The descriptor protocol, for routing specific attribute accesses to instances of classes with arbitrary get and set handler methods, and the basis for other tools such as properties and slots.

Properties

The property protocol allows us to route a specific attribute’s get, set, and delete operations to functions or methods we provide, enabling us to insert code to be run automatically on attribute access, intercept attribute deletions, and provide documentation for the attributes if desired.

attribute = property(fget, fset, fdel, doc)

A First Example

class Person: # Add (object) in 2.X

def __init__(self, name):

self._name = name

def getName(self):

print('fetch...')

return self._name

def setName(self, value):

print('change...')

self._name = value

def delName(self):

print('remove...')

del self._name

name = property(getName, setName, delName, "name property docs")

bob = Person('Bob Smith') # bob has a managed attribute

print(bob.name) # Runs getName

bob.name = 'Robert Smith' # Runs setName

print(bob.name)

Setter and deleter decorators

class Person:

def __init__(self, name):

self._name = name

@property

def name(self): # name = property(name) "name property docs"

print('fetch...')

return self._name

@name.setter

def name(self, value): # name = name.setter(name)

print('change...')

self._name = value

@name.deleter

def name(self): # name = name.deleter(name)

print('remove...')

del self._name

bob = Person('Bob Smith') # bob has a managed attribute

print(bob.name) # Runs name getter (name 1)

bob.name = 'Robert Smith' # Runs name setter (name 2)

print(bob.name)

del bob.name # Runs name deleter (name 3)

__getattr__ and __getattribute__

The __getattr__ and __getattribute__ methods are also more generic than properties and descriptors—they can be used to intercept access to any (or even all) instance attribute fetches, not just a single specific name.

In short, if a class defines or inherits the following methods, they will be run automatically when an instance is used in the context described by the comments to the right.

def __getattr__(self, name): # On undefined attribute fetch [obj.name]

def __getattribute__(self, name): # On all attribute fetch [obj.name]

def __setattr__(self, name, value): # On all attribute assignment [obj.name=value]

def __delattr__(self, name): # On all attribute deletion [del obj.name]

A first example

class Catcher:

def __getattr__(self, name):

print('Get: %s' % name)

def __setattr__(self, name, value):

print('Set: %s %s' % (name, value))

X = Catcher()

X.job # Prints "Get: job"

X.pay # Prints "Get: pay"

X.pay = 99 # Prints "Set: pay 99"

A second example

class Person: # Portable: 2.X or 3.X

def __init__(self, name): # On [Person()]

self._name = name # Triggers __setattr__!

def __getattr__(self, attr): # On [obj.undefined]

print('get: ' + attr)

if attr == 'name': # Intercept name: not stored

return self._name # Does not loop: real attr

else: # Others are errors

raise AttributeError(attr)

def __setattr__(self, attr, value): # On [obj.any = value]

print('set: ' + attr)

if attr == 'name':

attr = '_name' # Set internal name

self.__dict__[attr] = value # Avoid looping here

def __delattr__(self, attr): # On [del obj.any]

print('del: ' + attr)

if attr == 'name':

attr = '_name' # Avoid looping here too

del self.__dict__[attr] # but much less common

print('---------start--------')

bob = Person('Bob Smith') # bob has a managed attribute

print(bob.name) # Runs __getattr__

bob.name = 'Robert Smith' # Runs __setattr__

print(bob.name)

del bob.name # Runs __delattr__

Example: __getattr__ and __getattribute__ Compared

class GetAttr:

attr1 = 1

def __init__(self):

self.attr2 = 2

def __getattr__(self, attr): # On undefined attrs only

print('get: ' + attr) # Not on attr1: inherited from class

if attr == 'attr3': # Not on attr2: stored on instance

return 3

else:

raise AttributeError(attr)

X = GetAttr()

print(X.attr1)

# 1

print(X.attr2)

# 2

print(X.attr3)

# get: attr3

# 3

class GetAttribute(object): # (object) needed in 2.X only

attr1 = 1

def __init__(self):

self.attr2 = 2

def __getattribute__(self, attr): # On all attr fetches

print('get: ' + attr) # Use superclass to avoid looping here

if attr == 'attr3':

return 3

else:

return object.__getattribute__(self, attr)

X = GetAttribute()

print(X.attr1)

# get: attr1

# 1

print(X.attr2)

# get: attr2

# 2

print(X.attr3)

# get: attr3

# 3

Management Techniques Compared

The following first version uses properties to intercept and calculate attributes named square and cube.

class Powers(object): # Need (object) in 2.X only

def __init__(self, square, cube):

self._square = square # _square is the base value

self._cube = cube # square is the property name

def getSquare(self):

return self._square ** 2

def setSquare(self, value):

self._square = value

square = property(getSquare, setSquare)

def getCube(self):

return self._cube ** 3

cube = property(getCube)

X = Powers(3, 4)

print(X.square) # 3 ** 2 = 9

print(X.cube) # 4 ** 3 = 64

X.square = 5

print(X.square) # 5 ** 2 = 25

# Same, but with generic __getattr__ undefined attribute interception

class Powers:

def __init__(self, square, cube):

self._square = square

self._cube = cube

def __getattr__(self, name):

if name == 'square':

return self._square ** 2

elif name == 'cube':

return self._cube ** 3

else:

raise TypeError('unknown attr:' + name)

def __setattr__(self, name, value):

if name == 'square':

self.__dict__['_square'] = value # Or use object

else:

self.__dict__[name] = value

X = Powers(3, 4)

print(X.square) # 3 ** 2 = 9

print(X.cube) # 4 ** 3 = 64

X.square = 5

print(X.square) # 5 ** 2 = 25

# Same, but with generic __getattribute__ all attribute interception

class Powers(object): # Need (object) in 2.X only

def __init__(self, square, cube):

self._square = square

self._cube = cube

def __getattribute__(self, name):

if name == 'square':

return object.__getattribute__(self, '_square') ** 2

elif name == 'cube':

return object.__getattribute__(self, '_cube') ** 3

else:

return object.__getattribute__(self, name)

def __setattr__(self, name, value):

if name == 'square':

object.__setattr__(self, '_square', value) # Or use __dict__

else:

object.__setattr__(self, name , value)

X = Powers(3, 4)

print(X.square) # 3 ** 2 = 9

print(X.cube) # 4 ** 3 = 64

X.square = 5

print(X.square) # 5 ** 2 = 25

Delegation-based managers revisited

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, job=None, pay=0):

self.name = name

self.job = job

self.pay = pay

def lastName(self):

return self.name.split()[-1]

def giveRaise(self, percent):

self.pay = int(self.pay * (1 + percent))

def __repr__(self):

return '[Person: %s, %s]' % (self.name, self.pay)

class Manager:

def __init__(self, name, pay):

self.person = Person(name, 'mgr', pay) # Embed a Person object

def giveRaise(self, percent, bonus=.10):

self.person.giveRaise(percent + bonus) # Intercept and delegate

# def __getattr__(self, attr):

# return getattr(self.person, attr) # Delegate all other attrs

## def __repr__(self):

## return str(self.person) # Must overload again (in 3.X)

def __getattribute__(self, attr):

print('**', attr)

if attr in ['person', 'giveRaise']:

return object.__getattribute__(self, attr) # Fetch my attrs

else:

return getattr(self.person, attr) # Delegate all others

sue = Person('Sue Jones', job='dev', pay=100000)

print(sue.lastName())

sue.giveRaise(.10)

print(sue)

tom = Manager('Tom Jones', 50000) # Manager.__init__

print(tom.lastName()) # Manager.__getattr__ -> Person.lastName

tom.giveRaise(.10) # Manager.giveRaise -> Person.giveRaise

print(tom) # Manager.__repr__ -> Person.__repr__

Decorators

Coding Function Decorators

The following defines and applies a function decorator that counts the number of calls made to the decorated function and prints a trace message for each call.

class tracer:

def __init__(self, func): # On @ decoration: save original func

self.calls = 0

self.func = func

def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs): # On call to original function

self.calls += 1

print('call %s to %s' % (self.calls, self.func.__name__))

return self.func(*args, **kwargs)

@tracer

def spam(a, b, c): # spam = tracer(spam)

print(a + b + c) # Wraps spam in a decorator object

@tracer

def eggs(x, y): # Same as: eggs = tracer(eggs)

print(x ** y) # Wraps eggs in a tracer object

spam(1, 2, 3) # Really calls tracer instance: runs tracer.__call__

spam(a=4, b=5, c=6) # spam is an instance attribute

eggs(2, 16) # Really calls tracer instance, self.func is eggs

eggs(4, y=4) # self.calls is per-decoration here

Timing Calls

class timer:

def __init__(self, func):

self.func = func

self.alltime = 0

def __call__(self, *args, **kargs):

start = time.clock()

result = self.func(*args, **kargs)

elapsed = time.clock() - start

self.alltime += elapsed

print('%s: %.5f, %.5f' % (self.func.__name__, elapsed, self.alltime))

return result

@timer

def listcomp(N):

return [x * 2 for x in range(N)]

result = listcomp(5) # Time for this call, all calls, return value

listcomp(50000)

listcomp(500000)

listcomp(1000000)

print(result)

print('allTime = %s' % listcomp.alltime) # Total time for all listcomp calls

网友评论